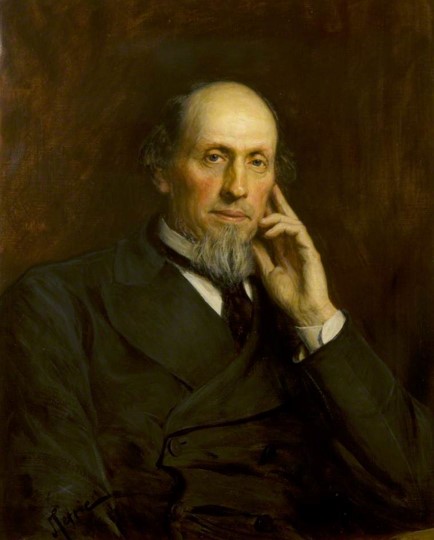

Orchar was the epitome of the late 19th century self-made man (1). Born in 1825 in Craigie, then a small hamlet on the outskirts of Dundee, his father was a master joiner and wheelwright whose family farmed land at West Ferry (2). In the 1840s Orchar was apprenticed as an engineer with Kinmond Hutton and Steele, based in Dundee’s Wallace Foundry (3). Following a period in Portsmouth, Orchar returned to Dundee in 1856 and formed his own partnership with draughtsman William Robertson basing their operation at the Wallace Foundry. The business partners were hugely successful and Robertson & Orchar were commissioned to design and build a number of engineering works throughout Dundee, Angus and Fife. The company’s wealth was further bolstered by the firm’s innovative design and construction machinery for the textile industries.

Throughout his career Orchar demonstrated a keen interest in civic politics and cultural improvements. His legacy to the city of Dundee and the Burgh of Broughty Ferry, an area well known for philanthropist industrialists, was extensive. In 1886 he was elected to Chief Magistrate of Broughty Ferry (re-titled Provost the following year) a position which he held until his death. Whilst in this role Orchar instigated a number of improvements to Broughty Ferry, including, in 1887 to mark Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, designing the ironwork and paying the substantial sum of £1000 for a new park entrance to Broughty Ferry’s Reres Hill; his friend the architect T.S. Robertson designed the stone archway. Two years later he purchased and established New Park (now known as Orchar Park) just south of Reres Park on Broughty Ferry’s Monifieth Road. He was also significantly involved in a number of charitable ventures including establishing a trust to aid orphans and widows of drowned fishermen (4).

Orchar was a highly respected figure in Dundee’s cultural scene. He was a talented violinist and golfer and was well known for his ‘racy old Scottish stories’ which he intended to publish with illustrations by McTaggart (5). As a collector of antique violins (he owned two by Stradivarius, a Joseph Guarneri and an Amati) he was a generous player: ‘During his lifetime he was every ready to lend them to players skilled enough to make proper use of them’(6) .

It is, perhaps, Orchar’s extensive knowledge of art which marks him as rare amongst his contemporaries. This interest saw him, in the 1840s, become first a drawing student and then tutor at Dundee’s Watt Institute located on Constitution Road. By the 1860s Orchar was a serious collector and was friends with many of the artists whose work he collected. Pettie was a regular visitor to Orchar’s Angus Lodge home and Orchar regularly travelled on painting trips with McTaggart including an 1882 tour of Europe where they visited Joseph Israëls.

Orchar’s interest in the educational value of art, of ‘seeing “the Beautiful”’ was paramount to his philanthropy (7). Recognition of his contribution to Dundee’s artistic and cultural surroundings was clearly evident in a banquet held in his honour, at the Queen’s Hotel, on the 14 January 1885. As Provost Ballingal noted in his invitation, Orchar’s deeds were ‘beyond an entry in a minute book, and a brief paragraph in the papers, no acknowledgement worthy of them has ever been made’ and it was hoped that ‘an address, and a dinner presided over by the Provost, might show that the citizens of Dundee are not unappreciative of services rendered so silently and unselfishly’(8). The banquet celebrated ‘the modest and unobtrusive spirit’ of Orchar and attracted a telegram from his friend Pettie: ‘Messrs Cameron, McWhirter, Hunter, Morris and Pettie, representing Mr Orchar’s friends in London, desire to be associated with you on this occasion to do honour to Mr Orchar. We convey our hearty good wishes to him’(9).

Dundee Fine Art Exhibitions

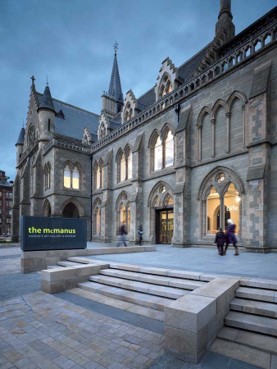

Exterior of The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum. Dundee Art Galleries and Museums.

Exterior of The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum. Dundee Art Galleries and Museums.

Interior of Victoria Gallery at The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum. Dundee Art Galleries and Museums.

Interior of Victoria Gallery at The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum. Dundee Art Galleries and Museums.

The celebration was certainly not faint praise. During the latter half of the 19th century Orchar was an important contributor to Dundee’s artistic circle. He lent 25 pictures to the 1867 British Association Exhibition held in the Volunteer Hall, Parker Square, Dundee and was a major contributor, lending 52 pictures, to the 1873 exhibition held in Sir George Gilbert Scott’s newly extended Albert Institute (now The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum) (10). By 1877 Orchar was a central figure on the management committee responsible for Dundee’s Fine Art Exhibitions, held regularly at the Albert Institute, which provided a major platform for Fine Art in Dundee over the next 14 years. In fact, so successful was the 1877 exhibition, attracting over 72,000 visitors during its three month opening, that it was only outstripped in size by that year’s Royal Academy summer show in London (11). Until 1889, along with T.S. Robertson, Orchar was joint convener of the selection and hanging committee after which he became the committee’s chairman. Regular exhibitions concluded in 1891 after it was decided that the ventures were becoming too expensive. One final exhibition was held, in conjunction with the annual exhibition of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour, in 1895 (12). Beyond the Fine Art Exhibitions Orchar was also involved with the Dundee Art Club and the Dundee Graphic Arts Association.

The Victoria Gallery

So central was Orchar’s association with Dundee’s art scene that it saw him collaborate, in the late 1880s, with the town architect William Alexander to design the Victoria Gallery extension of the Albert Institute. The proposal for an extension, to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, had long been mooted before it was finally opened in 1889. The gallery, which Orchar first built as a full scale model in his Wallace Foundry, was designed with the art works in mind; the walls were curved to angle the pictures for better viewing and the double skimmed glass roof helped to diffuse light (13).

Orchar died on the 14 May 1898 stipulating in his will that his entire art collection and his various books and violins be left for the benefit of the residents of Broughty Ferry on the occasion of the death of his wife (14). Catherine Orchar outlived her husband by a number of years dying on the 23 February 1916. In his will Orchar had also specified that his collection should be housed in a purpose built gallery. To this end he, along with T.S. Robertson, designed a gallery to be built in Orchar Park. Following the diminishing value of Orchar’s estate and the impact of the Great War the Trustees of Orchar’s estate decided that a purpose built gallery was financially impossible and Beach House, located on Broughty Ferry’s Beach Crescent, was purchased as a temporary home in 1919 (15). Only a small mention of Orchar’s proposed, and now lost, design in The Dundee Courier and Argus of the 21 May 1898 gives an idea of its structure:

The plan, of which Mr Orchar secured the custody, showed a building containing three halls lighted from the roof. At that time Provost Orchar had not intended to include as a gift to Broughty Ferry his violins, books, and the like. Now that he has included these, it will likely become necessary, when anything definite is to be done, to add another hall to the structure originally planned with the object of accommodating the books. (16)

Victoria Gallery, Albert Institute, c.1895. Wilson Collection WC6161. Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library.Victoria Gallery, Albert Institute, c.1895. Wilson Collection WC6160. Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library.Exterior of Albert Institute, c.1895. Wilson Collection WC0994. Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library.

Victoria Gallery, Albert Institute, c.1895. Wilson Collection WC6161. Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library.Victoria Gallery, Albert Institute, c.1895. Wilson Collection WC6160. Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library.Exterior of Albert Institute, c.1895. Wilson Collection WC0994. Local History Centre, Dundee Central Library.The collection was eventually transferred from Beach House to The McManus in 1987. Frustratingly, none of Orchar’s personal papers were transferred to the Trustees following his or his wife’s death and, as a result, it is difficult to establish when, where or from whom he purchased the artworks. It is known, however, that Orchar bought a number of prints during the Dundee Fine Art Exhibitions (see the entry on James Tissot’s Portico of the National Gallery, London for example). As a close friend of a number of painters it is also likely that he bought works directly from them and therefore no paperwork exists. It also seems probably that a number of works in the collection were also received as gifts. The label on the back of Samuel Bough’s 1886 painting Canty Bay states ‘Property of John Pettie, 21 St John’s, London’ which suggests Pettie gifted the painting to Orchar. William Ewart Lockhart’s The Jubilee Ceremony at Westminster, 21st June, 1887 is also an interesting addition. Only a limited number of prints were produced and, in the Dundee Fine Art Exhibition of 1891, an impression was exhibited as the ‘Property of Provost Ballingall’. Although possible, the likelihood of two impressions of Lockhart’s print being held in both men’s collection seems unlikely and it is therefore suggested that the print was gifted to Orchar sometime after the exhibition.

|

2 thoughts on “James Guthrie Orchar (1825-1898)”

Comments are closed.